Photo: Alice Rosati / Trunk Archive

Stories

Is Fat Still A Feminist Issue?

Popular culture loves to refer to psychoanalyst Susie Orbach as Princess Diana's therapist. But there is much more to her than that. Empowered by feminism, Orbach has been expanding our horizons since the 1970s with her insightful observations about the body, beauty culture, and what it means to be a woman. Today, we listen to her thoughts on how we perceive our bodies.

Text Seda Yılmaz

Have you ever found yourself locked in a battle with your own reflection? Or felt the need to monitor your diet and control how you look? In a society fixated on perfection, this is a struggle many of us know all too well. Susie Orbach, however, delves beneath the surface, unraveling the societal forces behind these seemingly personal struggles with body image. A renowned psychoanalyst, she is called Britain’s most famous therapist for treating Princess Diana in the 1990s. (And for avid fans of The Crown, she was featured in the series.)

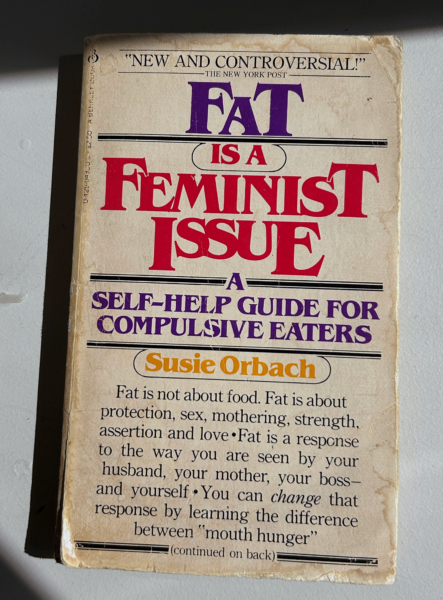

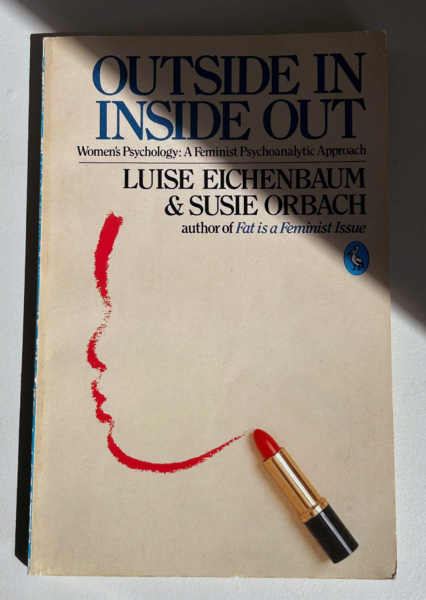

In the ’70s, amid the rise of second-wave feminism, Orbach co-founded London’s Women’s Therapy Center alongside her friend Luise Eichenbaum. Here, they offered therapy sessions to women, considering the impact of gender roles on mental health. Just two years later, with her groundbreaking book Fat Is A Feminist Issue she challenged entrenched stereotypes about women’s bodies and their relationships with food. In a world where women are boxed in by societal and cultural expectations, feeling content with their bodies seems like an ongoing battle. Yet, Orbach fearlessly challenges these norms, probing deep into the complexities of body image issues. From the struggles of eating disorders to the tyranny of beauty standards, she fearlessly navigates it all through a feminist lens. And her reflections on our modern-day perceptions of bodies and beauty are every bit as intriguing as her groundbreaking analyses of the past.

During our recent Zoom conversation with Orbach, I couldn’t help but notice a hint of concern in her voice. Despite her tireless efforts to foster self-acceptance, she’s troubled by the growing challenges of reconciling individuals with their bodies in today’s society. Nevertheless, her resilience shines through, offering us valuable lessons and perspectives.

You helped create a feminist approach to psychoanalysis back in the ‘70s and put body politics on the map with your groundbreaking book Fat Is A Feminist Issue. In the book’s preface, you explained how the era’s consciousness-raising groups and talking to women about how you felt about “bodies, being attractive, food, eating, thinness, fatness, and clothes” changed you dramatically. In your opinion, what are the gains of the decades-long struggles of feminists regarding body image issues?

I am not sure the gains are there. Because the pushback is so intense. Just today, while I was at the dental hygienist, she shared stories of young people in their twenties who had their teeth completely redone, which is really bad for their gums. From the time I wrote Fat Is A Feminist Issue, every part of the body has now been monetized or weaponized. While there has been progress for some, particularly those who are politically engaged, the vast majority, including women, girls, boys, and men, continue to face immense challenges. We are targeted all the time. I wish I could offer a more optimistic outlook, but unfortunately, that’s not the case.

You see, whether it’s cosmetics, food, so-called medicine, the fashion industry, health foods, or diet products, every arena encourages you to fix your surface. The pressure is to conform to what society deems appropriate.

In 2004, you were an adviser for Dove’s The Real Truth About Beauty, a global study on women, beauty, and well-being. In the research report, you stressed women’s desire for “a beauty that is full of variety.” Do you think the beauty culture has changed for the good over the years?

I believe there has been some slight change. When I look at girls and young women on the street, I see them adorning themselves and projecting confidence or whatever it may be. I’m not entirely sure about their internal experiences, but there seems to be a slight shift, a slight expansion.

Advertisements have become more diverse.

Yes, there’s a bit more representation of older women and individuals with physical differences. However, when you look at the portrayal of women in movies, unless they’re playing a character role, they are often pressured to become thinner and thinner. I’ve had people come to me asking how they’re supposed to manage their eating issues when they’re already quasi-anorexic.

Narrow beauty ideals put considerable pressure on women. What impact does the body positivity movement have on expanding these ideals?

I wish it had more power, but I don’t think it’s influential enough. It lacks the size and scope necessary to create significant change. Solidarity, fellowship, and a strong political movement around body positivity are important.

How do we feel more comfortable in our own bodies without getting too preoccupied?

I think we need to eat when we’re hungry, and stop when we’re full. Choosing real food over processed junk is crucial. I believe it’s also important to remember the purpose of our bodies—they’re meant to move, create, dance, make love, and laugh. We’re physical beings, not static objects. Instead of complimenting thinness, we should praise vitality, curiosity, or other internal qualities.

In your latest book Bodies, you mentioned that “we have entered a time of body destabilization.” Can you elaborate on this? How did we end up here?

Well, I believe we’ve ended up here because, traditionally, mothers have been primarily responsible for raising children, although fathers also play a role. However, mothers’ bodies have often been subjected to various forms of assault, whether by industries promoting beauty standards or through the aggression of patriarchy and misogynistic violence. What’s more, when women give birth, they face pressure to quickly return to their pre-pregnancy bodies. This creates a sense of anxiety and tension in their bodies as they navigate parenthood. They may project their fears onto their children. The traditional rhythm of caregiving spanning centuries has been disrupted by the bombardment of information from websites and groups, dictating every aspect of parenting instead of allowing for natural bonding and learning. If a mother has undergone a cesarean and simultaneously had a tummy tuck, viewing her body as a commodity rather than her home, she may transmit this anxiety about body image to her child.

Mothers often find themselves overwhelmed by conflicting information, unsure of what to do.

Absolutely. There’s so much pressure to bounce back after childbirth, to exercise, to do everything right, that mothers don’t have the opportunity to simply experience and bond with their babies.

You labeled body hatred as “one of the West’s hidden exports.” How can we break free of this hatred and allow our bodies to be good enough?

It’s akin to a post-colonial phenomenon, isn’t it? Instead of colonizing cotton fields or enslaving people, we’re now colonizing other bodies. These cultures are not just being influenced by Western bodies; they’re also being infiltrated by forms of capitalism that promise modernity. The notion of being part of the modern world is heavily tied to Western ideals. However, there are diverse modern worlds now—Korea, Africa—and they are shaping their own responses. But they are doing it in response to the imagery that has been pumped out by the West.

Do you believe there’s a way to overcome this body hatred?

I don’t think individual action is sufficient; it requires collective effort.

How do you think social media affects body image anxiety? Does it play a role in building solidarity and resisting beauty norms and body shaming?

People are constantly performing for the camera, even from a very young age. My grandchildren, for example, have learned to pose for the camera at the age of three.

Body modification practices, whether it’s tattoos or plastic surgery, often come with a rhetoric of empowerment and personal choice. What’s the right way to discuss this and question the cultural, economic and social forces behind it without being critical of the individual?

You can say, “I’m really interested in understanding why there’s such pressure to conform to certain beauty standards, and how much money is invested in these practices.” We don’t have to criticize individuals; we all understand the societal pressures at play. But it’s important to have conversations around the influence of capitalism and the institution of body hatred. We need to critique the larger societal structures that perpetuate body dissatisfaction.

Beauty practices can also bring pleasure. How do we find the balance between enjoying these practices and not being carried away with the beauty culture?

Everybody has to find their own response. For me, I find such practices boring now, whereas in my youth, I might have enjoyed facials.

How do you feel about aging?

I feel very angry that at nearly 80, I’m expected to look like 50. It’s not right. There are other meaningful activities to engage in, like reading a book, gardening, or pursuing interesting work. While you may still feel discontent about certain aspects of your appearance, there’s more to life than just that.

In recent years, celebrities have become more and more vocal about their mental health struggles and body image issues. The stigma around mental health has weakened, and we now have access to an abundance of information about it, particularly on social media. However, despite this increased awareness, mental health issues seem to be on the rise. Can greater awareness of mental illness make us more susceptible to experiencing symptoms and receiving diagnoses? What is your take on this?

Every generation has its own symptoms, right? I believe diagnoses are only useful as a tool for understanding one’s health. They offer an explanation, but they’re ultimately human constructs. Saying “I have a narcissistic mother” doesn’t truly convey much until you unpack what that means. While diagnoses may be helpful for some, they’re not the approach I typically favor.

I’ve had clients come to me saying, “I’ve got the boyfriend, the job, the apartment, and I’ve got this or that mental health issue.” It becomes a part of their identity.

Do you think it can also act as another oppressive force for people?

I think it’s a bit of both. If you say I have autism, you feel yourself to be understood or validated. It explains things to you. But if you remain focused on your symptoms and don’t try to struggle it can become oppressive. You’re not only your symptoms, are you?

This interview has been edited for clarity.