Photograph: Virgile Guinard

Fragrance

A Day In The Fields of Chanel

Valerie Dayan and Emine Boyner travel to Grasse to witness the artisanal and meticulous jasmine harvesting and extraction process. The Grasse jasmine has been an emblematic raw material for Chanel fragrances since 1921.

Text Valerie Dayan

Photos Virgile Guinard

Do you ever really think about the flowers? Where do they come from, who cultivates them, the lands they flourish in? What makes some of them extra special? Chanel does. Chanel really, really does. Olivier Polge, their in-house perfumer, spends his days discovering little perennial nuances that make up the brand’s fragrances, like N°5, one-of-a-kind classics. The May roses, iris pallida, jasmine grandiflorum, tuberose, and geranium rosat used in Chanel fragrance compositions are all cultivated and harvested in a family-owned estate in the Grasse area, directly collaborating with the French house since 1987. Grasse is known for having a uniquely fertile ground for cultivating the best fragrant version of flowers and has become a mecca for perfumery in the past centuries. It is where Chanel N°5 was born; as the creator of the original back in 1921, Ernest Beaux chose Grasse jasmine as one of the headlining raw materials. Locals of the region, the Mul family, are at the heart of Chanel’s floral ingredient journey in Grasse. With the vision of the previous in-house perfumer, Jacques Polge, they have partnered with Chanel since 1987. So far, five generations have played an active role in creating the finest floral raw materials.

In the fields of Chanel, jasmine’s harvest season is typically from August to October. It’s a brief period of diligent labor by the family, the gatherers, and the extraction specialists at the plant. It’s a period seasoned with freshly picked jasmine, a scent particular to the flowers grown in this region. It’s an olfactory moment that is hard to forget once your nose encounters such beauty. I know this for a fact. This September, I had the pleasure of physically witnessing the process in Grasse along with herbalist and dear friend Emine Boyner. As a person who is always fascinated by flowers (are they not the stars of the earth?) and processes (I know we live in a world that focuses mainly on the results, but I always think the journey there is the most special), I was overjoyed by being present to observe an ordinary day at the fields.

We arrived early at the fields, as the gatherers routinely start the picking with the sunrise. The September weather in Grasse has an enwrapping balmy quality: fresh, crisp, and warm at the same time. It’s the perfect day. Me and Boyner change into the Chanel rain boots arranged for us at the Bastide and head to the grounds where the jasmines bloom, where the distinct nature of Chanel fragrances come from. Fabrice Bianchi, the son-in-law of Joseph Mul, who initiated the rather natural collaboration between the fashion house and the family, now has an active role in the process. He elaborates on the daily and seasonal procedures of harvesting jasmines and admits that the little white flower with star-like petals are like children they raise to adulthood. “We are continually improving our techniques to lead our plants to the highest possible level of quality without ever taking the risk of depleting the soil. We let the fields lie fallow between crops, and we perform in-depth analyses to understand their language. Our aim is to produce the most fragrant flowers and to guarantee the same quality today and tomorrow.” Fabrice Bianchi also demonstrates the right way to pick the jasmines: A simple and sensible gesture that starts with gently grabbing the flower from the stalk and placing it in the palms. He explains that the hands must coordinate to pick from proximity to ensure practicality and speed. I replicate his technique and pluck a few. Boyner does, too, and places them in the micro basket hanging from her neck.

Meanwhile, the gatherers around us quietly concentrate on filling their raffia baskets with fresh crops. On a typical day, each gatherer picks about 2 kilos of jasmines to be transported directly to the factory. Approximately 350 kilos of jasmines are needed to produce 1 kilo of the highly aromatic concrete. And 1 kilo of this concrete yields 550 grams of jasmine absolute to be used in Chanel perfumes. I must admit that I had zero contribution to the process; the few jasmines I’ve gathered are now secretly drying up in a little notebook at home.

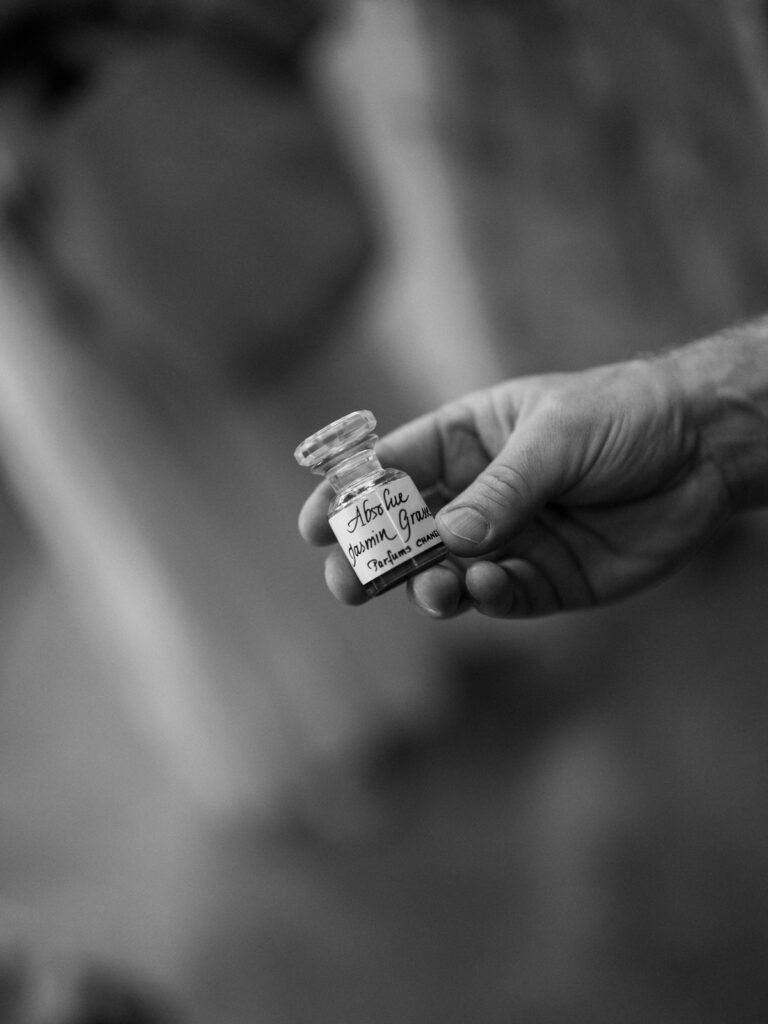

Following this fragrant experience that instilled a newfound respect and love for the raw material process, we met with Olivier Polge. We smell floral absolutes from the fields next door: Jasmin de Grasse, Rose de Mai Grasse, Iris de Grasse, Géranium de Grasse, and Tubéreuse de Grasse. Polge has us a whiff of the more common exotic jasmine, and the difference is discernible even to my amateur nose. The jasmines from the soils of Grasse are earthier, more delicate, balanced, and less narcotic. Polge says that when Coco Chanel and perfumer Ernest Beaux invented Chanel N°5, she wanted a floral bouquet where the nose could not detect specific flowers. Chanel’s was a relatively avant-garde approach to perfumery back when fragrances were typically composed around single ingredients. Polge likens the olfactory process’s precise, complicated, and highly artistic nature to that of a musical orchestra. “There is a specific tone or an instrument that, depending on the context in which you use them, can give a very different impression. It’s all about the blend.” With such deliberation of high-quality fragrance creation, is there a yearly limit to the number of Chanel N°5 bottles produced? “Yes, there is a limit,” Polge answers with an affirming smile. “There’s, unfortunately, a limit.”

After years of mindful alliance, Chanel and the Mul family have streamlined flower harvesting and extraction, and adding the factory in the fields in 1988 has been paramount. Olivier Polge’s father, Jacques Polge, has played a vital role in the upkeep of Chanel flowers, specifically the jasmines. “Jasmine production in Grasse was on a steady decline, and we feared we would no longer have enough for our formulas,” he says. “At the time, no one was concerned with replanting jasmine, so we conducted a scientific study to find a viable rootstock and bypassed the industry by controlling all of the links in the production chain, from growing the plant right through to its extraction.” After the gatherers finish the day’s crops, the jasmines in their baskets are weighed, placed into metal crates, and transferred directly to the plant in the middle of the fields. This plant is not only for extraction; it is also a fragrance laboratory for improving the raw materials. We watched crate after crate get welcomed into the factory, and with a perceivably innate enthusiasm of the specialists, they were unloaded in huge metal cylinders where they are absorbed in a volatile solvent that soaks up all the jasmine fragrance during extraction. Me and Boyner were invited to go in that very barrel. After witnessing all the labor and learning about all the passionate details of Chanel’s flower extraction, we hesitated. We didn’t want to harm any innocent jasmines. We were told we wouldn’t. The brief minute we were inside, the cylinder filled up with the crops of the day was celestial. We were thankful bystanders of the quasi-religious floral experience that is pivotal in making some of the finest and most iconic fragrances to exist.

Next time you spray on N°5, Gabrielle, or any other Chanel fragrance orchestrated by flowers grown in these fields, pause for a moment. Even if, for a brief second, think about all the love, labor, specific care, and minute yet significant details that go into making these perfumes unparalleled. It will be a moment of pure gratitude.

Previous

Previous